Undergraduate student assistant Julie Carr wrote this post as part of her work gathering titles of graphic biographies for the Modernist Remediations project.

While working studying graphic biographies in the Modernist Remediations project, I became interested in whether we could classify this emerging genre along conventional “brow” lines and whether that classification would yield any interesting results.

Van Wyck Brooks’ famous essay “America’s Coming-of-Age”, published in 1915, brought the terms “Lowbrow” & “Highbrow” into common usage, with “Middlebrow” later appearing in the early 1930s to accompany them (Swirski and Vanhanen, 3). These terms have traditionally been used as shorthand descriptors for both a piece’s artistic merit or sophistication and its social standing: “Highbrow” work can be understood as classy, refined, and elegant, while “Lowbrow” work is common, clumsy, and often crude, with “Middlebrow” work occupying the sort of cultural no-man’s-land that exists between the other two.

While not useless, these terms present… problems. Besides being inextricably linked to the racist pseudoscience of phrenology, from which they draw their vocabulary (Swirski and Vanhanen 35), each of these terms, over a past century of use, have absorbed additional connotations that we want to avoid in our classifications. To call a work “Lowbrow” today is not just to make a judgement about its aesthetics and sophistication, but at least to some degree its quality and validity as art (and vice-versa for “Highbrow” work). In classifying each graphic biography I catalogued, I was not considering subjective artistic merit; I was instead attempting to assign classifiers to each piece based off aspects such as target audience, art style, choice of subject, marketing, and general presentation, in order to gain a sense of how each piece positions themselves in relation to the society they exist in. In light of the problems associated with the previous terms, I’d like to introduce the alternative classifiers I’ve used to categorise the dataset, and will be referring to throughout the rest of this post:

- Broad-Appeal: Broad-appeal works tend to be aimed at large, non-specific audiences, with less complex writing than the other two categories & generally conventional art styles. They usually focus on entertainment value first and foremost, positioning themselves around telling intrinsically-entertaining stories about well-known figures in popular culture.

- Moderate-Appeal: Moderate-appeal works form a sort of bridge between Broad-Appeal and High-Level works, but still have a distinct identity of their own. They tend to be aimed at audiences that are still relatively broad, but more focused than the general public, ie. audiences looking to learn about a specific figure that might not be so well-known. They have a tendency to focus on informational/educational value (though this is not absolute), with art styles & writing complexity varying widely in service of this goal.

- High-Level: High-Level works tend to be aimed at small, specific, even niche audiences, generally those who hold a pre-existing interest in the work’s subject – who will often not be widely-recognized in pop culture. They almost universally maintain a strong focus on both complex, intricate art and high-quality writing, both of which almost always serve to support well-developed thematic aspects of the work. They tend to be focused around character or psychological studies of their subjects.

With our terms defined, let’s move on to the data!

Data

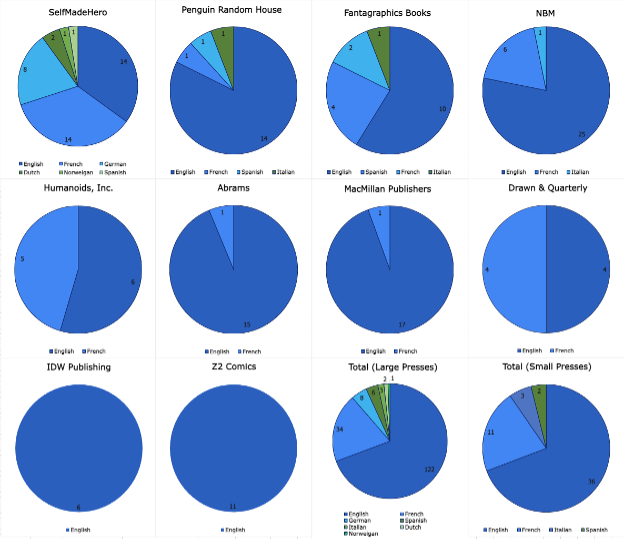

Upon a cursory glance at the figures for numbers of original English works vs. translated works, the first thing to notice is the vaguely bimodal distribution. It isn’t a perfect split, of course, but there is a clear separation: of the 10 major publishers that appear in the data (the first 10 charts in the above image), 6 were overwhelmingly focused on original English-language work, while 3 more were fairly evenly split, with 1 – SelfMadeHero – the outlier in their being primarily focused on translations. These relatively clear groupings perhaps suggest some sort of divide between original English-language works and translated works – put a pin in that.

Also of note is the consistency visible in the proportions of the last two graphs, which, respectively, display the combined values of the 10 large presses from the previous graphs and the combined values from the assorted small presses from the dataset that did not have large enough catalogues to be given their own charts. Both graphs display almost an exact proportion of 70% original English-language works as well as an additional 20% of works translated from French, with assorted translations making up the remaining 10%. This might indicate a relatively even playing field between smaller & larger publishers in terms of securing translation deals for foreign publications.

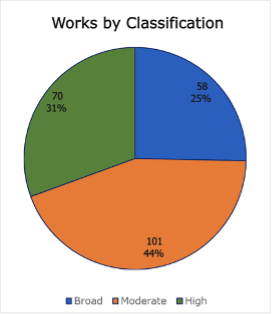

Looking at a breakdown of how each classification is represented within the data shows that no one category completely crowds out the others, and that Moderate-Appeal works make up a slim majority, as might be expected. Of note is that High-Level titles are actually represented more than Broad-Interest works. This caught me a bit off-guard, but perhaps offers some insight into how graphic biographies are carving out a niche for themselves within the market; the data appear to support the idea that graphic biographies are being perceived as a relatively “intellectual” category of title. Could this indicate an attempt on the part of creators to purposefully distance themselves from public perceptions of comic books (which have traditionally been considered “Lowbrow” or, under our system, Broad-Interest titles)?

To be continued in Part 2.

Works Cited

Swirski, Peter, and Tero Eljas Vanhanen, editors. When Highbrow Meets Lowbrow: Popular Culture and the Rise of Nobrow. Palgrave Macmillan US, 2017. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95168-0.