[CONTENT WARNING: HORROR, BONES, TENTACLES]

Oriane Edwards contributed two blog posts from her independent research on the Modernist Remediations project in ReMedia.

The rise of artificial intelligence-made art (AI art) tools such as Midjourney sparked fierce debates regarding the future of art. Beyond art, how might AI art itself be used more broadly as a space for reflection about algorithms and our relationship with these technologies?

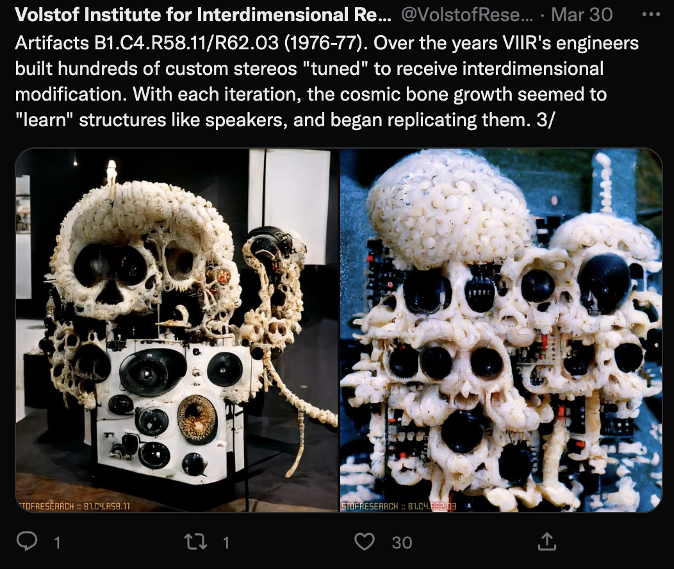

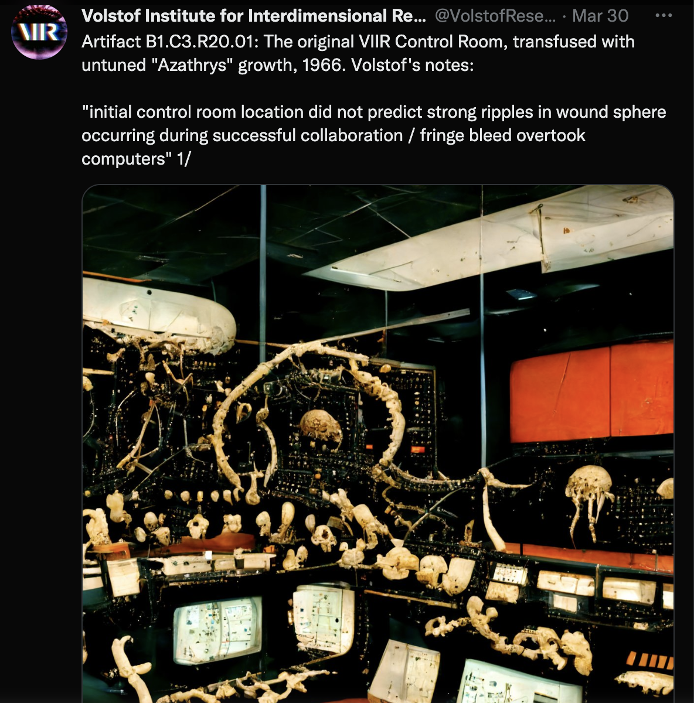

Rob Sheridan’s fictional docu-series, the Volstof Institute for Interdimensional Research (VIIR) is an example of a piece whose conceptual and artistic goals required the use of AI art generation. Sheridan, a prominent digital artist, was a beta tester for Midjourney. His initial test pieces expanded into a Twitter webseries. Sheridan describes the series as “cosmic horror”: a tale of arcane and frightening experiments run by mad scientists somewhere in the British Columbia wilderness. Believing they found a place “where the fabric of spacetime was wounded,” the scientists build a secret facility to research this collision between worlds. The story is told through fictionalized archival images and captions. Sheridan uses body horror prompts to generate the images using Midjourney, then writes fictional captions to accompany the images. The captions introduce characters and plot – detailing the scientists’ descent into madness and the destruction of their secret base.

The VIIR series is a reflection on the collaborative and otherworldly dimensions of artistic creation using AI. The experimentation process used by the VIIR scientists is a metaphor for the creation of AI art. The experiments are explicitly named as “collaborations.” The VIIR scientists use “custom electronic hardware” – (computers) that are “tuned” (given machine learning algorithms) allowing them to “absorb cosmic bleed” (ie. process and recombine information).

The otherworldly connection spawns organic growths that reproduce uncanny imitations of human objects, in the same way that AI art eventually learns and reproduces human-made data points. The scientists describe “bonelike” growths that “learned structures like speakers and began replicating them.” Yet, the growths are dependent on the electrical current supplied by the humans: “bone growth ceased when electronics failed / [they] do not wish to break the machines / they wish to collaborate.” The fusion of the alien organic matter and the humans’ machines is an inverse mirror of our own human bodies colliding with and growing alongside inorganic matter and algorithmic logic.

It may be that the heart of AI is collaboration, the “posthuman distributed agency” (Zeilinger 9) of a “cognitive assemblage” (Hayles 199). A cognitive assemblage is a self-reflexive system where distinct processes of absorbing and responding to information share agency in determining how the system processes stimuli. Cognitive assemblages are not neat or streamlined, they are “corporeal” and “messy” (Hayles 33), qualities that are viscerally represented in the VIIR documents. This corporeality is tantalizing, terrifying and ominous. There is a resonance between these emotions and contemporary affective responses to AI.

Humans remain transfixed by these creations. Just as past decades saw seductive properties ascribed to a “technological sublime,” the VIIR scientists mysticise the otherworldly forms. Laughing at the moon landing, they indulge in utopian visions of what “collaborations” may bring to humanity. Perhaps they see in this assemblage the “freedom to aggregate heterogenous objects, spaces, bodies… re-assembling the world anew” (Brown 303). Is then the ultimate dream and horror of generative technologies that they may re-assemble our world into a new form, theirs and ours (Marx 977)?

[For more visuals, here is the Volstof Institute Twitter – https://twitter.com/VolstofResearch]