Undergraduate student assistant Julie Carr wrote this post as part of her work gathering titles of graphic biographies for the Modernist Remediations project.

You can read Part 1 of this post here.

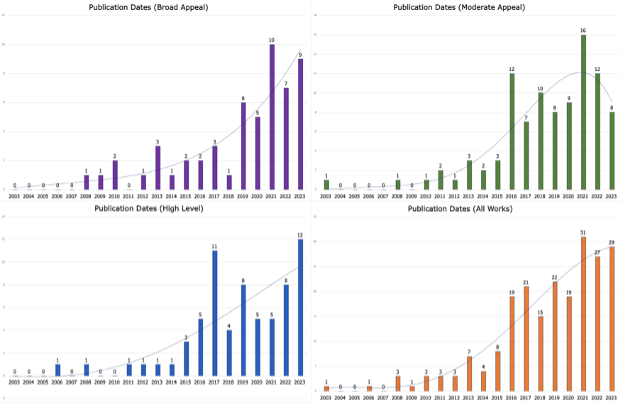

In the last post, I discussed insights from the “brows” or constructed markets that graphic biographies from different publishers fall into. In this post I’m interested in whether the timeline of publication might offer any insights into how graphic biographies construct high-level, moderate-appeal, or broad-appeal categories.

The release dates of various titles in the dataset don’t offer any particularly stunning revelations, mainly serving to confirm that the mid-2010s saw a massive wave in the popularity of graphic biographies that has yet to wane. One slightly interesting trend that can be spotted here is that Broad-Appeal works appear to have had some small advantages in early popularity before seeing a huge spike in 2019. My first thought is to wonder if we might be looking at some kind of attempt by publishers to “catch up” to the newfound popularity of Moderate-Appeal and High-Level titles by latching onto what they could have perceived as a passing trend at the time, but I don’t know that I noticed any qualitative indicators in the Broad-Appeal titles I catalogued as releasing around that time to support this.

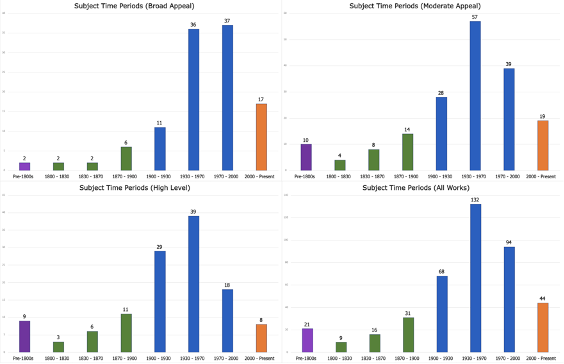

Digging into some more granular data that has been sorted by category is where things start to get really interesting. This is one of those instances where Moderate-Appeal works can clearly be seen acting as a sort of bridge between High-Level and Broad-Appeal works: Broad-Appeal works have a clear focus on the Mid-to-Late 20th centuries, with some interest in the 21st century but a clear drop-off for anything before the 1930s, in contrast to High-Level works, which we can see focus predominantly on the Early-to-Mid 20th centuries, with Moderate-Appeal works splitting the difference (and, interestingly, appearing fairly close to the overall average values).

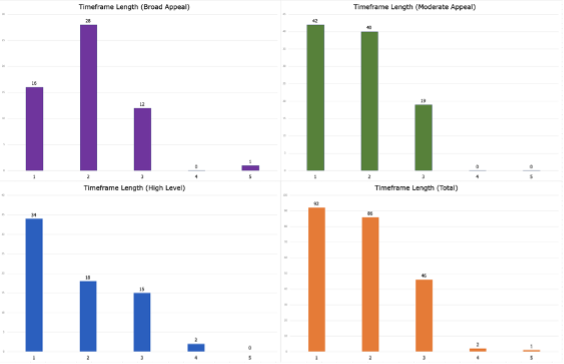

The length of time covered by each piece also presents some interesting trends, with something that I wasn’t expecting being High-Level titles’ clustering towards a focus on short timelines and a tight focus on a well-defined period – especially when contrasted against Broad-Appeal works (tending to focus on more general areas of their subjects’ life) and Moderate-Appeal works (a fairly even split between tight focus and more general coverage). Interestingly, we can see the same “bridging” effect happening here from Moderate-Appeal titles, with their values quite closely resembling the overall averages of the entire dataset.

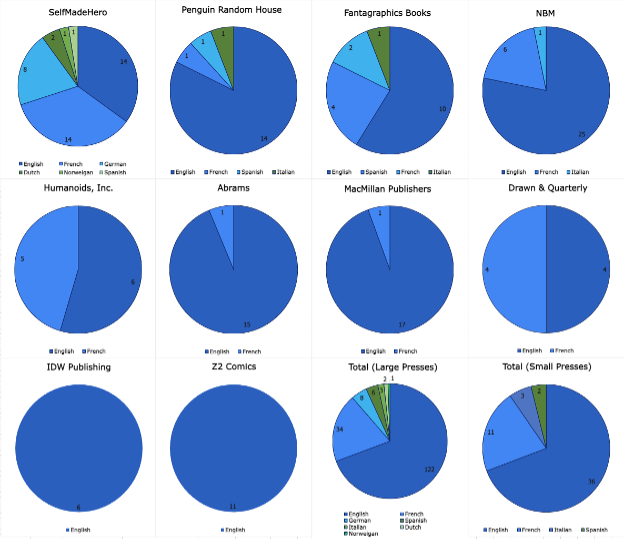

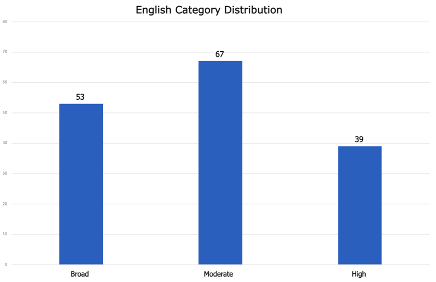

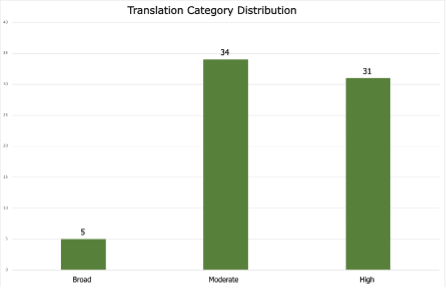

Remember that pin about works in translation from before? Examining the differences between categories of English-original titles and translated titles, we can see that divide between English-original and translated titles pop up again. The English categories form a relatively even distribution, in contrast to the translated categories, which astonishingly feature almost no Broad-Interest works at all. I find this absolutely fascinating but also wonder if there might be some sort of selection bias effect at play here regarding the works that are chosen to be translated into English in the first place. If the market for translations is competitive then it stands to reason that the works that make it through could be pre-filtered for a certain level of complexity or uniqueness. This might also be a reflection of Bande Dessinées, a unique comics tradition that originates and is still popular in France and the Benelux region of Europe. Bande Dessinées have been around for decades and present a rich, varied cultural history that has evolved almost completely separately from the culture of North American comics – perhaps we’re seeing the effects of this tradition in our data.

A common theme that appears to recur throughout the dataset is that of two main groupings: High-Level works that primarily serve to offer narrow, focused looks at figures from the mid-20th century and earlier, and Broad & Moderate-Appeal titles that primarily appear to focus on more well-rounded overviews of figures from the mid-20th century and later. Although it’s impossible to say for sure at this point, it appears that an important difference exists between the ways in which the first category engages with their subjects (mainly as historical figures, with a certain amount of distance from our present day) and the way the second category engages with theirs (mainly as figures that the reader will likely have at least some preconceived notions about and be familiar with, and who may still even be alive). Moving forward, I’d be interested in investigating to what degree this distinction underpins our understandings of the graphic biography as a potential emerging genre: is there room for both of these groups in whatever definition we come up with for the genre? If not, should there be?